Learning Objectives

This is an intermediate to advanced level course. After

completing this course, mental health professionals will be able to:

- Discuss the history and prevalence of ADHD in adults.

- Describe how the symptoms of adult ADHD represent a disorder of executive functioning and self-regulation.

- List

the steps in the assessment of adult ADHD.

- Explain

the role of clinical judgment in the evaluation of ADHD in

adults.

- Summarize two evidence-based therapies for management of ADHD symptoms and

associated executive functioning deficits in adults.

- Discuss two categories of FDA-approved medications for use with adults with ADHD.

- Provide specific recommendations to assist the adult client with ADHD in achieving more effective functioning in major life activities such as work, school, home management, and managing finances.

The

materials in this course are based largely on and adapted from the following

books by Dr. Barkley: Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Handbook

for Diagnosis and Treatment (4th ed., 2015, New York: Guilford

Press), ADHD in Adults: What the Science Says (2008, Guilford Press), Taking Charge of Adult ADHD (2021, New York: Guilford Press), and When an Adult You Love Has ADHD: Professional Advice for Parents, Partners, and

Siblings (2016, Washington, DC: Lifetools, American Psychological

Association Press). But other sources were used as well, many of which

can be found in the Resources and References sections at the end

of this course.

The course contains the most accurate information available to

the author at the time of writing. The scientific literature on ADHD grows

daily, and new information may emerge that supersedes these course materials.

This

course will equip clinicians to advise adults with ADHD and their loved ones on

the most effective methods for managing the symptoms of ADHD and associated

impairments in adults with ADHD.

Outline

- Introduction

- Brief

History of ADHD in Adults

- Prevalence

of Adult ADHD

- What

is the Nature of ADHD?

- Diagnostic

Criteria and Adjustments for Adults

- ADHD

Involves Executive Functioning Deficits

- How Do We Know ADHD Is a Disorder of Executive Function?

- Is Neuropsychological Testing Useful for Diagnosing Adult ADHD?

- Diagnosing Adult ADHD

- The

Important Role of Clinical Judgment

- Impairments:

What Are the Consequences of Untreated ADHD?

- Major

Life Domains

- Comorbid

Disorders

- Conclusion

to Impairments Linked to Adult ADHD

- Addressing

Reactions to the Diagnosis

- Helping

the Client Understand and Accept Their Diagnosis

- Acceptance

and Ownership Do Not Mean Making Excuses

- Becoming

Educated About Adult ADHD

- Evidence-Based

Therapies

- General

Counseling

- EF-Focused

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

- Coaching

- Medication

Management

- Other Issues in Using Medications for Adult ADHD

- Promising

but Under-Investigated Therapies

- Routine

Physical Exercise

- Marital/Couples

Counseling

- Vocational

Assessment and Counseling

- Technology

- Mindfulness

Meditation

- General

Strategies for Managing Adult ADHD

- ADHD

is a Disorder of Performance, Not of Knowledge

- Reject

Treatments that Don’t Address the “Point of Performance”

- Mental

Information Does Not Guide Behavior Very Well

- ADHD

Means Being Blind to Time

- ADHD

Reduces Internal or Self-Motivation

- Manage

the External Environment to Manage the Symptoms

- Rules

Alone Don’t Guide Behavior Very Well

- View

ADHD as the Diabetes of Psychiatry – A Chronic Disorder that Can Be Effectively

Managed

- Specific

Strategies for Assisting Adults with ADHD in Major Life Activities

- Work

and School Settings

- Managing

Health Risks

- Driving

- Substance

Abuse

- Conclusion

- Appendix

- Available FDA-approved Treatments for ADHD

- The Eight Stimulant Delivery Systems

- Resources

- References

Introduction

Despite

great strides in the identification, referral, diagnosis, and management of

adult ADHD over the past three decades (Faraone et al., 2024), much work remains to be done by mental

health professionals to further improve the delivery of mental health services

to most adults with ADHD. This course seeks to help ameliorate that situation

by briefly reviewing the nature, diagnosis, comorbidity, and impairments associated

with ADHD. It then provides both an overview of the evidence-based approaches

currently available for the management of adult ADHD as well as myriad specific

recommendations for the management of the various domains of impairment that

are a consequence of adult ADHD.

Beginning

in the 1990s, thanks to several large follow-up studies with adults, both the

general public and many mental health professionals became aware that ADHD was

not just a disorder of children but persisted into adulthood in at least 50%-65%

of all cases diagnosed in childhood. Moreover, evidence began to accumulate

that ADHD could be diagnosed in 3%-5% of the U.S. adult population. Many of

these cases had never been diagnosed as such in childhood even though they

likely had the condition. A major US population survey conducted in 2006

reported that 90% of those meeting diagnostic criteria for adult ADHD had never

been diagnosed with it or received any treatment for it. And just 25% were

receiving any treatment for any mental health condition. Yet the survey found

these adults to be suffering impairment in several major life activities. Now,

more than a decade later, the situation for adults with ADHD has and continues

to improve, although the majority are likely still not receiving appropriate

diagnostic and treatment services specifically for their ADHD. More mental

health professionals are now well aware that adults can have ADHD, and many are

seeking more information about its identification, diagnosis, and management. That

is the purpose of this course: to assist in providing up-to-date continuing

education training in how to recognize and treat ADHD in adults.

A Brief History of ADHD in Adults

The

history of ADHD is extensive for the childhood stage of the disorder. Far less

information exists concerning the history of ADHD in adults, largely because throughout

most of the past century ADHD was widely held to be a disorder strictly of

childhood. While popular interest in the possibility that adults can have Attention

Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) most likely originated with the

bestseller Driven to Distraction, published in 1994 by psychiatrists

Edward Hallowell and John Ratey, clinical and scientific papers acknowledging

the existence of an adult version of this disorder date back at least 50 years,

possibly even two centuries.

The

first paper in the medical literature on disorders of attention that described

a condition highly similar to ADHD is a short chapter in a German medical

textbook by Melchior Adam Weikard in 1775. Weikard described symptoms of

distractibility, poor persistence, impulsive actions, and inattention more

generally in both adults and children. The next reference to adult ADHD was in the

medical textbook by the Scottish physician, Dr. Alexander Crichton, in 1798. He

discussed two attention deficits, one of which is very similar to adult ADHD

while a second dealt with low levels of arousal, alertness, and energy that may

be similar to the increasingly studied second attention disorder known now as cognitive disengagement syndrome (previously called

sluggish cognitive tempo). Crichton espoused the view that inborn forms of

inattention would diminish with age in some though not all cases. Noteworthy as

well was that Crichton felt that problems with attention were associated with

many other mental and physical disorders, and that there are different

components involved in attention, making it multidimensional rather than

unitary, as modern researchers now also believe.

We must skip 104 years ahead to find the next reference to attention disorders in the medical literature. In his series of three published lectures to the Royal College of Physicians, George Still (1902) described 43 children in his clinical practice having serious problems with sustained attention and in the moral control of their behavior. By the latter symptom, Still meant the regulation of behavior relative to the moral good of all. He viewed the latter construct as a conscious comparative process in which one evaluates both the present and likely future consequences of one’s actions for both one’s self and for others prior to choosing a course of action. Most of his cases were not just inattentive and lacking in forethought but also were quite overactive. He proposed that the immediate gratification of the self was the “keynote” quality of these and other attributes of the children. In addition, among all of them, passion (or heightened emotionality) was the most commonly observed attribute and the most noteworthy. Still noted further that a reduced sensitivity to punishment characterized many of these cases, for they would be punished, evenly physically, yet engage in the same infraction within a matter of hours. Still believed that the major “defect in moral control” so typical of these cases was relatively chronic. While it could arise from an acquired brain defect secondary to an acute brain disease, and might remit on recovery from the disease, in most cases it was chronic.

Here

again we see reference to the possibility that ADHD may persist into adulthood,

thereby logically opening the door to the possibility that adults can possess

this same pattern of symptoms dating back to childhood.

The

first papers on research studies involving adults having actual ADHD seem to

date to the late 1960s. At that time, the disorder was known as Minimal Brain

Damage or Dysfunction (MBD) and its likely existence in adults was supported by

three sources. The first of these was the publication of several early

follow-up studies demonstrating the persistence of symptoms of

hyperactivity/MBD into adulthood in many cases. The second source was the

publication of research showing that the parents of hyperactive children were

likely to have been hyperactive themselves and to suffer in adulthood from

sociopathy, hysteria, and alcoholism, not to mention the usual symptoms of inattention,

lack of impulse control, and excess activity levels, all of which logically

implies that ADHD could exist in adults. The third source directly supporting

such a conclusion was the publication of studies on adult patient samples that

were believed to have hyperactivity or MBD. Noteworthy for our purposes here

was the finding that such adults had an early history of

hyperactive-impulsive-inattentive behavior dating back to childhood and that was

highly predictive of placement in an adult group characterized as impulsive-destructive,

again implying a persistent course of this behavioral pattern from childhood to

adulthood.

Adults

in the studies were typified by marked difficulties concentrating, being

emotionally labile, fearing their loss of impulse control, and showing marked

irritability as well as anxiety and self-depreciation. Problems with poor motor

skills and sluggish reaction or response timing were noteworthy. While EEG and

neurological exams were normal for gross findings of hard neurological signs,

all showed evidence of “soft” signs of “neuro-integrative disturbances” such as

motor clumsiness, poor balance, confused laterality, and poor coordination.

Psychological testing also revealed evidence of perceptual-motor problems and

motor incoordination and timing.

Especially noteworthy was the large clinical study by Anneliese Pontius (1973) of more than 100 adult cases of MBD. She noted that many demonstrated hyperactive and impulsive behavior and that their disorder likely arose from frontal lobe and caudate dysfunction. Such dysfunction would lead to their “inability to construct plans of action ahead of the act, to sketch out a goal of action, to keep it in mind for some time (as an overriding idea) and to follow it through in actions under the constructive guidance of such planning” (p. 286). Moreover, if adult MBD arises from dysfunction in the frontal-caudate network, it should also be associated with an inability “to reprogram an ongoing activity and to shift within principles of action whenever necessary” (p. 286). She went on to show that indeed, adults with MBD demonstrated such deficits indicative of dysfunction in this brain network, making this the first paper to argue that adult ADHD was likely a disorder of the brain’s executive function networks – a conclusion supported decades later by neuro-imaging and neuropsychological research.

By

the mid-1970s, researchers investigated the efficacy of stimulants with adults

having MBD using double-blind, placebo-controlled methods to assess response to

methylphenidate, pemoline (another stimulant), and the antidepressants

imipramine and amitriptyline. Paul Wender (1976) was likely the first to do such studies. About two thirds of cases showed a favorable

response to either the stimulants or antidepressants. Yet, it would not be

until the 1990s that both the lay public and the professional field of adult

psychiatry would begin to seriously recognize the adult equivalent of childhood

ADHD on a more widespread basis and to recommend stimulant or antidepressant

treatment in these cases.

By

the mid-1990s, Paul Wender set forth explicit criteria for the manner in which

the diagnosis of ADHD in adults should be made, recognizing that nether the diagnostic

criteria proposed for the syndrome of childhood hyperactivity in 1968 nor the

later Attention Deficit Disorder in 1980 were developmentally appropriate for

adult patients. Wender proposed an approach for diagnosis of ADHD in adults

(Wender, 1995) that was subsequently used in a number of research projects,

especially medication trials. Patients and an additional informant, preferably

a parent, were to be interviewed to assess retrospectively the childhood

diagnosis of ADHD. Evidence was also to be obtained for ongoing, continued

impairment from hyperactive and inattentive symptoms. Seven symptoms were

proposed to characterize the phenomenology of adult ADHD, namely, 1)

inattentiveness; 2) hyperactivity; 3) mood lability; 4) irritability and hot

temper; 5) impaired stress tolerance; 6) disorganization; and 7) impulsivity.

Known as the “Utah criteria,” these diagnostic guidelines required a

retrospective childhood diagnosis, ongoing difficulties with inattentiveness and hyperactivity, and at least two of the remaining five symptoms. A rating scale

was also constructed to aid in the retrospective diagnosis of childhood ADHD. The

Utah criteria have declined in use among investigators and clinicians in favor

of using DSM-5-TR criteria that have been adjusted for use with adults.

A

further watershed moment in the history of adults with ADHD was the development

and FDA approval of the first medication for adult ADHD, the non-stimulant atomoxetine

(Strattera®), by the Eli Lilly & Company. It was investigated in thousands

of adults with ADHD in several randomized, placebo-controlled trials and found

to be useful for its management. Later, stimulants (methylphenidate, mixed

amphetamine salts) would eventually be studied more thoroughly for use with adults

with ADHD and receive similar FDA approval for such. New delivery systems have

also been subsequently developed that permit greater sustained therapeutic

action across the day than did immediate release preparations. These include

osmotic pumps (Concerta®), variable timed-release pellets (Focalin XR®, Metadate

CD®, Ritalin LA®, Adderall XR®, et al.), and skin patches (Daytrana®), besides

the earlier-available but clinically disappointing wax-matrix sustained release

formulation of methylphenidate (Ritalin SR®).

More

recently, a new non-abusable formulation of a mixed amphetamine compound (Vyvanse®)

received FDA approval for use with ADHD. In this delivery system, the pills must be dissolved and then absorbed through the gut before the amphetamine compound can be activated and available for therapeutic blood levels to become available and thus manage adult ADHD symptoms. By late 2018, yet another delivery system was FDA-approved, this one being a delayed onset version of methylphenidate that can be taken at night and that reliably activates the next morning, about nine hours after ingestion (brand name awaiting assignment). The company may have plans to use the same delivery system for an amphetamine-based delayed onset medication in the future.

Psychological

treatments for adults with ADHD, though numerous in clinical practice, have to

date not received as much serious scientific scrutiny as medications. This

remains a glaring deficiency in the clinical scientific literature on the

disorder in adults, though it is improving of late. Cognitive behavioral

therapies focusing specifically on adult ADHD symptoms and associated deficits in executive function (EF) have been developed by

Safren and colleagues, then of the Harvard Medical School, independently by

Ramsay and Rothstein at the University of Pennsylvania Medical School, and most recently by Solanto and colleagues now at Montefiore Medical Center in Long Island, NY. All focus to varying degrees on the executive function deficits associated with ADHD

Prevalence of Adult ADHD

It

appears from both childhood follow-up studies and, more directly, from studies

of adult general population samples, that the prevalence of ADHD in adults in

the United States is approximately 5%. Based on this figure and the 5%

estimated prevalence for ADHD in adults, it seems likely that at least 14

million adults in the US probably have ADHD. This is a sizeable number, making

it imperative that the mental health, medical, and educational professions, as

well as employers, become more aware of the existence of this disorder and its

treatments.

It

also makes it essential that we understand as much about the expression of this

disorder in adulthood – along with its comorbid psychiatric disorders and

impairments in major life activities – if we are to be able to better

understand the disorder and to be able to manage it and its consequences more

effectively.

What is the Nature of ADHD?

ADHD

is recognized in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

(5th edition, or DSM-5-TR, 2022) as a neurodevelopmental

condition that consists of developmental delays or deficiencies in at least two

significantly related domains of neuropsychological abilities. These two

dimensions are referred to as inattention and hyperactive-impulsive symptoms (Faraone et al., 2024).

Readers

should understand that despite the criticisms and limitations I will level at

these criteria, at least as they pertain to the diagnosis of adults, they are

the most empirically-based, rigorously tested, and logically coherent criteria

of their time for the diagnosis of ADHD, especially in children.

The Symptoms of ADHD

The DSM-IV criteria specified a set of 18 symptoms divided into two lists; inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity, on which were nine symptoms each. These symptoms have to occur often or frequently and been present for at least six months. In the subsequent DSM-5-TR published in 2022, the same 18 symptoms continued to be employed but they have been given clarifications in parentheses for use with adolescents and adults. The age of onset has now been adjusted upward to age 12 given that the earlier age seven had no scientific validity to it. By increasing the age of onset of the disorder, it was hoped that more adults who otherwise meet all other criteria for the disorder except the age of onset of seven years old will now be eligible for the diagnosis; a good thing. The threshold for the diagnosis remained at six symptoms on either list for children and is reduced to five for adults. This too is an improvement, although most studies on this issue would suggest that four symptoms would be even better.

A further improvement is the explicit recommendation that symptoms reported by patients be corroborated through someone who knows the patient well. Also beneficial has been the removal of the subtyping scheme such that ADHD is now viewed as a single disorder in the population, which behavioral genetic studies of large populations clearly suggest. Clinicians can now specify which symptoms are more evident in the clinical presentation at the time of assessment, such as Predominantly Inattentive Presentation. Still, some problems remain with the DSM criteria that were not addressed in DSM-5-TR. But that is not to imply any stability for that presentation or qualitative differences from the other presentations, as cases can move from one to the other presentation over time and development.

Diagnostic Criteria and Adjustments for Adults

There is little evidence to suggest that ADHD symptoms currently identified in the DSM-5-TR, designed as they were for use with children, best characterize adults with ADHD. My colleague, Kevin Murphy, and I (and others) identified nine symptoms that were the most useful for identifying adults with ADHD, six of which were not in the DSM-5-TR but came from our evaluation of executive functioning in daily life using my rating scale of that domain. The proposed criteria are:

Has four of the first seven, or six of all

nine of the following symptoms that have persisted for at least six months to a

degree that is maladaptive and inconsistent with the subject’s developmental

level:

- Often easily distracted by

extraneous stimuli

- Often makes decisions impulsively

- Often has difficulty stopping

activities or behavior when they should do so

- Often starts a project or task

without reading or listening to directions carefully

- Often shows poor follow-through on

promises or commitments they have made to others

- Often has trouble doing things in

their proper order or sequence

- Often more likely to drive a motor

vehicle much faster than others (excessive speeding) (If person has no driving

history, substitute: “Often has difficulty engaging in leisure activities or having

fun quietly.”)

- Often has difficulty sustaining

attention in tasks or leisure activities

- Often has difficulty organizing

tasks and activities

Some of the above symptoms that cause

impairment were present before age 18. Some impairment from these symptoms

is present in two or more settings (e.g., work, educational activities, home

life, social functioning, community activities, etc.). And there must be clear

evidence of clinically significant impairment in social, academic, domestic

(cohabiting, financial, child-rearing, etc.), community, or occupational

functioning.

Another

problem with DSM-5-TR is that the greatest weight is given to inattention (nine

symptoms), followed by hyperactivity (six symptoms), with the remaining three

symptoms thought to reflect impulsiveness. Most of those impulsive items

reflect principally verbal behavior. The words “impulsive” or “poorly

inhibited” are not even mentioned in the symptom list despite being viewed

currently as a core feature, if not THE core feature of this disorder. This has

proven to be a glaring oversight because the symptom of “makes decisions

impulsively” and others related to it (acts before thinking, has difficulty

waiting for things, etc.) are among the most discerning symptoms for

distinguishing ADHD from other psychiatric disorders as well as from the

general non-disordered population. While DSM-5-TR tested additional symptoms of impulsivity,

it was elected not to include them, perhaps due to concerns that it would

increase the prevalence of the disorder.

In order to make the original DSM-IV symptoms more specific to adults, given that they were developed originally just for children, the DSM committee added clarifications to many items in parentheses. Our research on these clarifications, however, shows that they are only weakly related to the original symptom they are supposed to clarify and behave more like new or additional symptoms of ADHD. A few may be as or more related to anxiety as they are to adult ADHD. It is therefore possible that in using these clarifications, one is actually using a list of symptoms far larger than the original 18 items, thus making the cutoff score of five symptoms on each list questionable as the cutoff point for determining presence of disorder. Not doing so could lead to diagnosing a larger percentage of adults with this disorder than would be the case with the earlier DSM-IV criteria. In short, one cannot add more symptoms to the list and not adjust the cutoff score accordingly. For these reasons, I recommend ignoring the clarifications in parentheses and just using the original DSM item wording when evaluating adults until more research can clarify the validity of these item clarifications.

Also

problematic in DSM-5-TR is the requirement for the age of onset of symptoms to be by

age 12. Unlike the assessment of children, the clinical evaluation of adults is

highly dependent on patient self-reporting. However, adults have a limited

recall of the exact time course and nature of symptoms within the developmental

time frame associated with so precise a childhood onset and have a limited

recall of the domains of childhood impairments related to those symptoms.

Moreover, many adults who present for clinical care are unable to provide independent

evidence of the disorder, either through retrospective parental report or

records of academic functioning. Adults do not typically come to clinical

evaluations with their parents in order to provide the customary evidence for

judging symptom onset as is done in children.

Add

to this the likelihood that ADHD may create a positive illusory bias in adults

concerning their possible impairment – as it does in children with ADHD – that

could possibly diminish self-awareness of symptoms and impairments. This gives

a further reason to question the reliance upon adult patients for establishing

the age of onset of their symptoms and associated impairments. I argue that the

criterion should be abandoned or redefined to include the broader period of

adolescence to young adulthood (ages 18 to 24). No evidence is available in the literature to our

knowledge that suggests that onset of ADHD symptoms at or after age 12 results

in a qualitatively or even quantitatively different disorder than cases of ADHD

having the earlier recommended symptom onset (Vater et al., 2024). And my own research showed that

ages 12-18 would have been even more sensitive to and inclusive of those with an otherwise legitimate disorder.

A

further limitation of the DSM-5-TR for use with adults is that it requires that

some impairment from the symptoms is present in two or more settings (e.g., at

school or work and at home). Problematic here, obviously, is that adults are

involved in far more numerous and important adaptive settings or domains of

major life activities than this criterion stipulates. Not only are the settings

specified here too global to be of much good to the clinician evaluating

domains of impairment (e.g., “home”), but they ignore many more domains of

major life activities that are not only more specific but also comprise

important domains of adult adaptive functioning. General functioning within the

larger organized community (e.g., participation in government or formally

organized community groups, cooperation with others living in the same

neighborhood, abiding by laws, driving), financial management (e.g., banking,

credit, contracts, debt repayment), parenting and child-rearing (e.g.,

protection, sustenance, financial and social support, appropriate education,

discipline), marital functioning, and routine health maintenance activities are

additional domains of major life activities in which symptoms may produce

impairment that would not be evident in children. Current criteria fail to

reflect these potential areas of impairment.

A

further difficulty with DSM-5-TR is that controversy exists over the definition of

impairment due to an enormous increase in requests for special accommodations

in employment and high-stakes academic testing under the Americans with

Disabilities Act (ADA). Further specification of the meaning of impairment in

DSM-5-TR is necessary so as to avoid misunderstandings among clinicians and public

agencies. Some clinicians assess impairment based on comparison of deficits

relative to a person’s intellectual level, much as had been done in the earlier

history of defining learning disabilities as being significant discrepancies

between IQ and some specific area of academic achievement, such as reading.

Others believe impairment is based on how well an individual functions relative

to their specialized peer group, particularly if they are unusually intelligent

or well-educated, such as fellow gifted individuals or peers in medical or law

school.

Still

others have argued that impairment should mean serious dysfunction in the performance

of major life activities (e.g., family, marital, social, or occupational

functioning) that are required of society in general. More to the point, this

view holds that impairment should be defined as being relative to the norm or

average person, as required by the ADA, and not relative to some narrow, highly

specialized and accomplished subset of adults or to an estimate of one’s

general cognitive ability, such as IQ. I prefer the latter view of defining

impairment because of a number of factors: its consistency with scientific

views on valid mental disorders (harmful dysfunctions that are failures or

severe deficiencies in mental adaptations as noted by Jerome Wakefield [1992]);

its consistency with the ADA, with associated court rulings, and with the

legislative intent behind the ADA (granting protections and accommodations to people

functioning well below normal or average); and simple fairness or justice –

individuals should not be viewed as disordered and granted special protections,

accommodations, disability financial benefits, or other societal privileges

when they are not below the average of the population at large. It is

inherently unfair to grant advantages to those who are not actually subnormal.

Also, this latter view of impairment respects the fact that one’s intelligence

is not an indicator of functioning in all avenues of adult life nor are

disparities between IQ and some other measure of adaptive functioning. The

DSM-5-TR should have made the criteria for impairment clearer as to the domains it

encompasses and the comparison group to be used for its determination.

Despite

these continuing problems with the DSM-5-TR criteria for adults with ADHD, the

changes that were made to DSM-IV are an improvement and make DSM-5-TR more

sensitive to the detection of the disorder in adults than its predecessor DSMs.

Even so, readers need to be alert to these limitations as they go about

applying DSM-5-TR criteria to the diagnosis of ADHD in adults.

Other

points to keep in mind in using DSM-5-TR are as follows:

- As we will see shortly, there are far more cognitive deficits linked to ADHD

hiding behind these two dimensions than their names imply. The disorder is

classified as neuro-developmental because the scientific evidence for

the substantial role of neurological and genetic causes in ADHD is now

overwhelming and irrefutable. ADHD is considered to be neuro-developmental because

it is primarily the result of a delay or lag in specific mental abilities and

it arises during the developmental course of the individual, most often before

16-18 years of age. Those deficits are largely due to delays and/or

dysfunctioning in the maturation of the brain areas that underlie EF.

- Such brain maldevelopment seems to arise largely from genetics, but can also

occur as a consequence of damage or other disruptive influences experienced by

the person at any time during development, most often during prenatal brain

formation (Faraone et al., 2024). Thus, ADHD can arise de novo in an adult as a consequence of

brain injuries even after development is completed, such as may occur secondary

to repeated closed head trauma, tumor, stroke, or other adverse events that

impact the functioning of brain regions and circuits known to support EF and

self-regulation (largely the prefrontal lobes and networks).

- ADHD presents largely the same in both sexes, despite popular opinions to the contrary (Babinski, 2024; Babinski & Libsack, 2025). That said, females were grossly underdiagnosed in earlier decades for various reasons and so the rise in diagnoses in females of late is positive news. And while the symptoms may be largely the same between males and females, there are significant differences in the nature of the comorbid disorders that link up with ADHD in each sex as well as differences in the domains of impairment likely to be affected. Moreover, symptoms in females may fluctuate far more dramatically across the month and likely the lifespan as a result of changes in the sex hormones in females (Ang et al., 2024; see also, Harper & Lewis, 2025).

The symptoms of ADHD are dimensional in that they reflect the extreme end of a

continuum (most likely a bell-shaped distribution) of normal or typical human

ability in these two areas. Therefore, adults with ADHD have a disorder that:

- is

beyond their own choice or making;

- is

intrinsic to their psychological and physical nature;

- is

not a categorical condition, such as being pregnant, but is dimensional;

- differs

primarily from the behavior and abilities of others in these dimensions as a

matter of degree (quantitative), not of kind (qualitative);

- will

most likely become evident sometime during childhood development (probably

before age 16 in 98% of cases);

- is

likely to be pervasive across many but not necessarily all situations;

- is

likely to be persistent over time for many but not necessarily all cases; and

- leads

to impairment in one or more major domains of life activities.

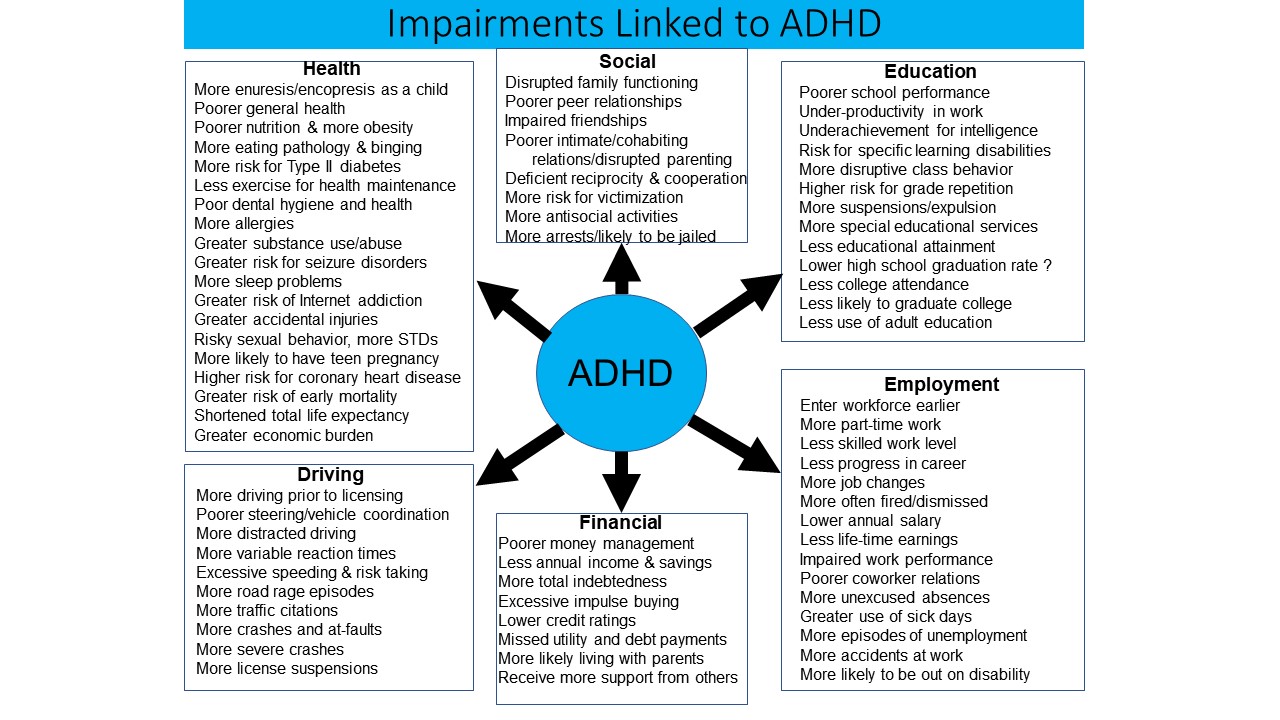

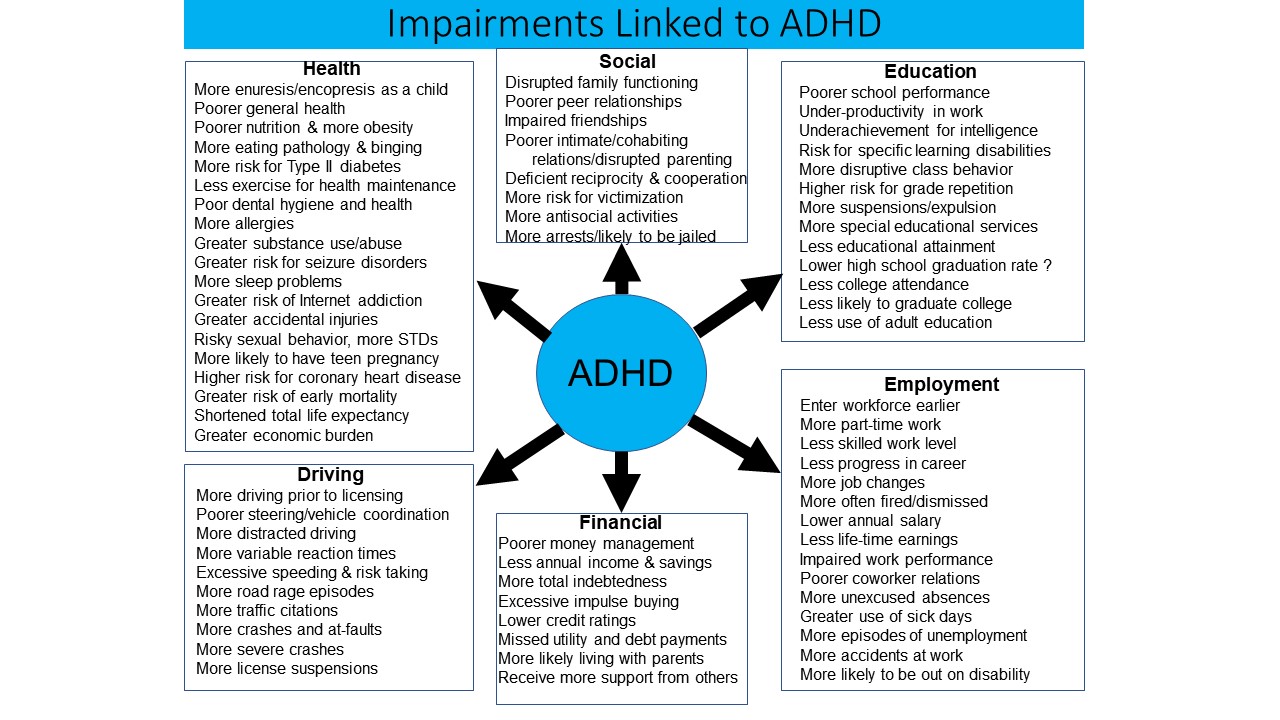

In summary, it is important to understand the nature of adult ADHD and its need for treatment. For one reason, as noted above, a substantial percentage of adults in the U.S. have ADHD (one in every 20-25). For another, they will be increasingly presenting to outpatient clinical services for diagnosis and management of their disorder as public awareness of adult ADHD continues to increase. Moreover, they are likely to be suffering impairments in many domains of major life activities (see Consequences of Untreated ADHD, below) given the important role of EF in adult daily life.

Without identification and treatment, ADHD in adults will contribute to their experiencing increased harm or suffering to themselves as well as to society and may likely underlie the reason they are not benefiting much if at all from treatments aimed at the other disorders that may coexist with adult ADHD (substance use, marital problems, occupational difficulties, driving impairments, weight control and health maintenance, etc.). Unmanaged adult ADHD may also be costing society billions of dollars annually as a consequence of these unaddressed or under-addressed impairments and comorbidities.

For these reasons, this course will provide readers with information on the outcomes of unmanaged ADHD in adults as well as review the treatment options that can help to reduce or eliminate these impairments.

ADHD Involves Executive Functioning Deficits

Many clinical researchers, myself included, conceptualize ADHD and its symptoms as involving deficits in the following mental abilities, often referred to as executive functions (see Dr. Barkley’s course on this website on Executive Functioning (EF), Executive Functioning: Critical Issues for Understanding and Managing Deficits).

Self-regulation (SR) relies on executive function and its underlying brain networks. Therefore, ADHD could also be called EFDD (executive functioning deficit disorder). The reason I prefer the term SRDD (self-regulation deficit disorder) is that it is the obvious and repeated failure to demonstrate self-regulation that is so apparent to those with ADHD, their families, and clinicians who are trying to evaluate and manage it.

Goal-directed

persistence and resistance to distraction (inattention)

What

separates the attention problems seen in ADHD from those evident in other

disorders such as depression is that those with ADHD have problems with

sustaining attention to and persisting toward a goal, either self-imposed or

assigned by others – in short, they suffer in their attention to the future.

They are less able to persist at getting things done over time, in time, and on

time that involve delayed or future events. Thus, they pay attention to what is

happening now just fine but not to what they need to be doing to be ready for

what is coming next or what they have been assigned to do. Even if they try to

persist toward tasks or goals, they are more likely than others to react to

distractions, which are events that are not relevant to the goal or task. Those

distracting events are not just irrelevant things occurring around them, but

also irrelevant ideas occurring in their mind. The problem here is not one of

detecting those distractors as well as others do, but in failing to inhibit

reacting to those distractors as well as others.

The EF-SR theory can further enlighten us as to the nature of the inattention occurring in ADHD; this is incredibly illuminating for clinically understanding ADHD but also for its differential diagnosis from other mental disorders that adversely affect attention, but in entirely different ways. Consider that attention represents a relationship between a stimulus and the perceptual-motor response of the individual who orients to it, explores it, and then may stay engaged with it. Attention therefore represents a form of stimulus control. But just what kinds of stimuli or events are failing to control or elicit such engagement from people with ADHD compared to other types of such stimuli or events?

Those with ADHD have little trouble paying attention to the now – the momentary present and external environment; in fact, that's the problem. What is going on immediately in front of them in that moment has a much stronger pull on engagement of their responses than do the private, mental representations about the tasks they have been asked to do or the future they plan for them and the behavioral sequences or schemas needed to make that future happen. Those mental representations are held in the two working memory systems – visual and verbal. Thus, what people with ADHD are inattentive to are those mental representations – about tasks, goals, time, and delayed consequences and the future in general – which are thus far less able to capture or control the actions of the individual with ADHD. Such representations are simply not compelling enough to govern their immediate behavior relative to the events playing out around them.

Reframing the inattention of those with ADHD in this way can vastly improve differential diagnosis, helping us distinguish between the inattention seen in ADHD and that seen in many other psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders. Disorders such as depression, anxiety, or even autism spectrum disorder can also result in a type of inattention. But people with these disorders are inattentive to events or stimuli in the now – just the opposite of ADHD. That type of inattention is now called Cognitive Disengagement Syndrome (see Becker, et al., 2022). In that case, mental representations (thoughts) about their problems, worries, fears, or just their daydreams or mind wandering (as in autism) are all too powerful in capturing and sustaining the engagement of the individual, decoupling the attention of the person from the external world and shifting it to a focus on mental events. People with these other disorders are mentally preoccupied instead of engaged with the ongoing flow of the now and the things on which they should be working. You can see this in the mental rumination of depression, in memory re-experiencing as in anxiety or PTSD, in self-absorption over possible adverse consequences that might happen to them, improbable as they are likely to be, and certainly in the obsessions of someone with OCD. Likewise, people suffering from the new attention disorder of sluggish cognitive tempo may be preoccupied simply with mental daydreaming or mind wandering to the point that it is maladaptive or pathological.

In sum, where people with ADHD are decoupled from being governed by thoughts and plans related to tasks and goals (the future), and thus overly attentive to the external now, those having other disorders are decoupled from events in the external world and overly attentive to mental events or thoughts.

Working

memory

A

large part of the adult’s inattentiveness in ADHD comes from the inability to

hold in mind what goal they have chosen or been assigned, what steps are involved,

the most efficient sequence for attaining that goal, and monitoring when it has

been accomplished. This reflects a deficiency in working memory, which is remembering

what to do. Memory for facts, knowledge, or information is not so much the

problem as is remembering what is to be done and persisting at it until it is

completed. Even if they try to hold in mind information that is to guide their

behavior toward a goal or task, such as instructions or assignments clinicians

give them, any distractions occurring around the adult with ADHD will disrupt

and degrade this special type of memory. The mental chalkboard of working

memory is wiped clean by the distraction and so the affected adult is now off

doing something other than what they are supposed to be doing. And having

reacted to a distraction, and so gone “off-task,” the adult with ADHD is far

less likely to re-engage the original and now-uncompleted goal or task. In sum,

the adult with ADHD is less likely than others to remember what they were

supposed to be doing. Yes, adults with ADHD are forgetful. But it is a special

type of forgetfulness – it is forgetting what they are supposed to be doing

(forgetting the goal, specifically, and the future more generally).

Inhibition

Adults

with ADHD are not just impulsive (poorly inhibited) in their actions, which

leads them to move around, touch things, and otherwise behave too much (the “Hyperactivity”).

Their deficit in inhibition extends to their verbal behavior (talking excessively)

and to their cognitive activities or thinking (impulsive decision-making). It

also interferes with their self-motivation, meaning that they are more likely

to opt for immediate rewards or gratification than others do. Put another way,

they have a high time-preference and so steeply discount the value of a future

or delayed event or consequence (reward or punishment) more than others do –

they prefer to have small results now rather than larger results later.

Finally, their impulsiveness is evident in their emotions. They display their

emotional reactions more quickly and more often than do others of their age.

And, if strong emotions have been provoked by some event, they will have a far

more difficult time moderating or otherwise self-regulating that emotion. So

adults with ADHD are less patient, more easily frustrated, quicker to become

emotionally aroused, more excitable, sometimes sillier, yet also more likely to

react with anger. And so the adult with ADHD is more likely to respond with

aggression when provoked. They show emotions that are less mature and

appropriate to the situation and less consistent with or supportive of their

future welfare than others do.

Planning

and Problem Solving

ADHD

is associated with difficulties in generating multiple possible options for

overcoming obstacles encountered when pursuing goals, or in contemplating

multiple solutions posed by problems. A related deficit is in the ability to

construct and execute the steps of a plan necessary to attain a goal. This

difficulty is often evident in school or work settings in problems with mental

arithmetic, providing verbal narratives to questions posed by others, and in

rendering oral reports, written reports, and other tasks in which a complex,

well-organized response is necessary.

A

recurring theme here is that ADHD interferes with thoughts, actions, words,

motivations, and emotions aimed at organizing behavior across time and

preparing for the future instead of just reacting to the moment. To act

impulsively, fail to persist, and be distractible is to be nearsighted toward

the future – to be preoccupied by moments and so be blind to time. The

aforementioned cognitive deficits will then disrupt the adult’s EF in daily

life activities, as will be evident in problems with:

- Self-Awareness – less able to

monitor their own activities, report accurately on their own behavior and

performance, and describe their inner states and outward behavior as reliably

or accurately as others.

- Self-Restraint – deficient

behavioral inhibition, limited self-control, poor delay of gratification, and

difficulties subordinating one’s immediate interests and desires to those of

others.

- Self-Management

to Time – poor time management and organization across time to achieve one’s goals or

accomplish assigned tasks.

- Self-Motivation – an inability to

activate and sustain motivation to continue relatively boring, tedious,

effortful, or lengthy tasks in which there is no intrinsic interest or

immediate payoff.

- Self-Organization

and Problem-Solving – difficulty with organizing one’s personal space,

desk, locker, academic materials, etc. so as to accomplish work efficiently and

effectively. Forgetfulness of what is to be done or what was assigned. Also,

deficits evident in tasks that require working memory and thoughtful problem-solving,

as noted above.

- Self-Regulation

of Emotions – difficulty with inhibiting the expression of impulsive emotions in reaction

to emotionally provocative events. This is evident in being easily excitable,

prone to both positive and negative emotional outbursts, and

greater-than-typical impatience, frustration, anger, hostility, and reactive

aggression.

How Do We Know ADHD Is a Disorder of Executive Function?

As the great neuroscientist Joaquin Fuster so eloquently argued in his 1997 book on the prefrontal lobes, the quintessential function of that brain region is the formation of goals and the cross-temporal construction, organization, and maintenance of behavior needed to attain desired goals, or what constitutes a hypothetical future. In other words, the role of executive function is to allow us to behave in ways that serve the future we want. So, if what we see in ADHD at a much deeper level than inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity is a deficit in self-regulation, it must be rooted in problems with these executive functions. And, in fact, neuroanatomy tells us that is so.

The Neuroanatomy of ADHD

The areas of the brain most reliably associated with ADHD are the prefrontal cortex, the anterior cingulate, the basal ganglia (especially the striatum), the cerebellum (especially the central vermis), and the amygdala (not always reliably implicated). Research demonstrates that these regions are functionally interconnected to form one of the seven major brain networks – the executive system. In my view, that system underlies the human capacity for self-regulation and, as Fuster concluded, for the cross-temporal organization of behavior toward goals (future-oriented action). There are at least four subnetworks in the executive network, each of them associated with different parts of the brain, that can help us understand how executive functions help us self-regulate – or, in the case of ADHD, make it difficult to do so:

- The Inhibitory Executive Network: Think of this subnetwork as allowing us to resist responding to goal-irrelevant events, or distraction. It's responsible for the voluntary inhibition of ongoing behavior and emotions, as well as the suppression of competing responses to goal-irrelevant events, both internal and external.

- The "What" or Cold Executive Network: Essentially, this network allows what we think about (mainly imagery and self-talk) to guide what we do. It also permits the higher-level function of the manipulation of goal-related mental representations (analysis and synthesis, or mental play) so as to support planning and problem solving.

- The "When" (Timing) Executive Network: When we choose to act can be as or more critical to the success of a plan than what we had planned to do, and it's this subnetwork that gives us a subjective sense of time and the temporal sequencing of thought and action as well as the timeliness in executing such actions.

- The Hot (Emotional) or "Why" Executive Network: This is probably the subnetwork that makes the final decisions about goal choices and the selection of planned actions to attain them. But it also permits the top-down regulation of emotion in the service of those goals and our longer-term welfare, probably through the use of self-imagery and self-talk, or the working memory network above.

You may be wondering where hyperactivity fits into the executive function neuroanatomy picture of ADHD. In part, it certainly arises from defective functioning of the inhibitory network. But in addition to the subnetworks listed in the sidebar is the motor activity regulation network. Disturbances in this network are thought to also give rise to the hyperactive symptoms of the disorder.

If what you are seeing in a patient includes problems with goal-directed attention and volitional inhibition, resistance to distraction, working memory (forgetfulness in daily activities), sense of time and timing, time management, planning and problem-solving, self-organization, emotional self-regulation, self-motivation, and self-awareness – essentially the major executive functions – and not just the traditional DSM-5-TR ADHD symptoms, then a patient may well qualify for a diagnosis of ADHD and certainly has executive function deficits underlying them. When you see this in patient after patient, with ADHD it is easy to come to see that, logically, ADHD must be EFDD at its root.

What does this mean clinically? It means that:

- ADHD comprises a far broader array of cognitive and behavioral deficiencies than is reflected in the current clinical view as set forth in the DSM-5-TR. To call this merely an attention disorder is both to trivialize the condition and to be clinically unproductive.

- You need to listen for the deficits in the various executive functions as you interview patients about these executive function domains, going beyond a mere exploration of just the DSM-5-TR ADHD symptoms.

- It is this broader array of executive function deficits that accounts for the range of impairments that people with ADHD experience across most domains of major life activities.

- These executive function deficits are the things that will require accommodations and other treatments well beyond what might be suggested from the traditional ADHD symptom dimensions.

Because the executive function subnetworks functionally interconnect – that is, they interact in varying ways from patient to patient – ADHD will be heterogeneous across cases. Don't expect symptomatic presentations to be identical or even highly similar. When you know that some networks may be more (or less) adversely affected by the various etiologies of ADHD than others, you know that close scrutiny will be required by the astute diagnostician to appreciate the diversity of clinical symptoms patients may demonstrate.

The

vast majority of adults meeting diagnostic criteria for ADHD fall in the bottom

7% of the population in each of these major areas of EF in daily life. It is

easy to see how such deficits would produce a myriad of difficulties with

functioning in various major life activities that typically place a premium on

these EF abilities. Those are the areas of daily functioning that adults with

ADHD are most likely to describe as problematic for them. So clinicians should

be listening carefully for complaints that fall into these areas when they

initially evaluate an adult with ADHD or are working with them initially in a

counseling or coaching circumstance.

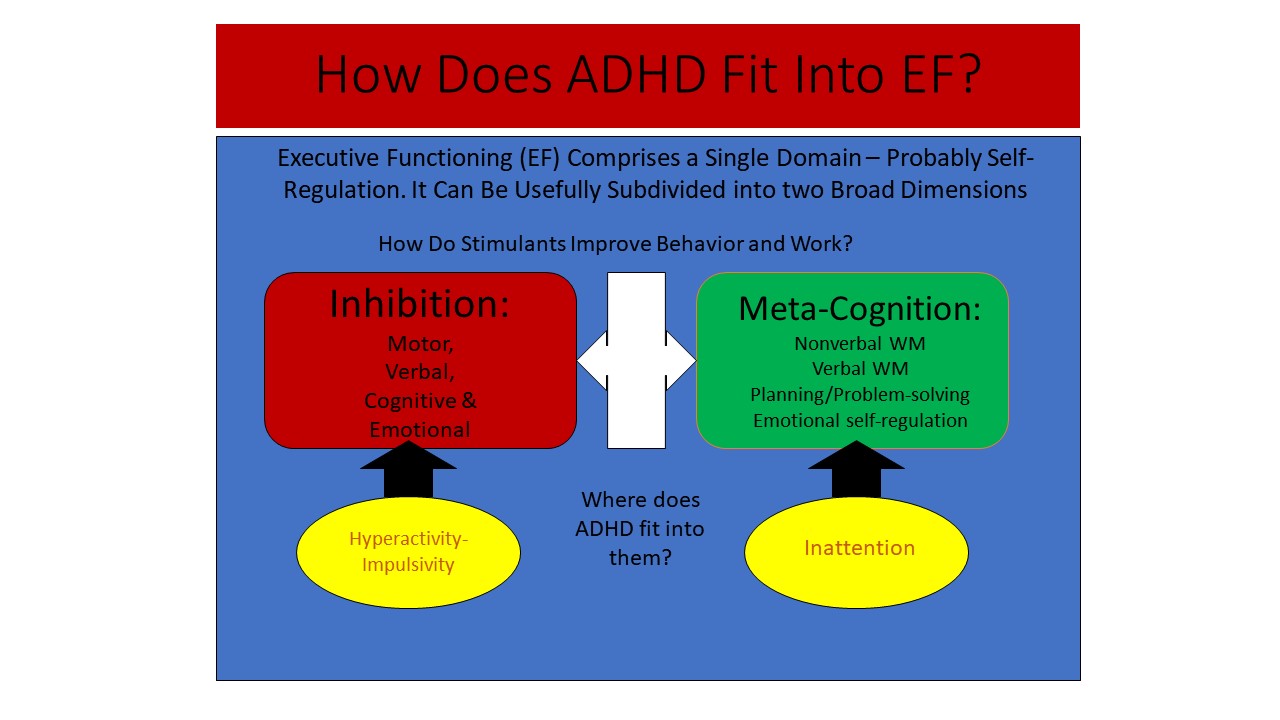

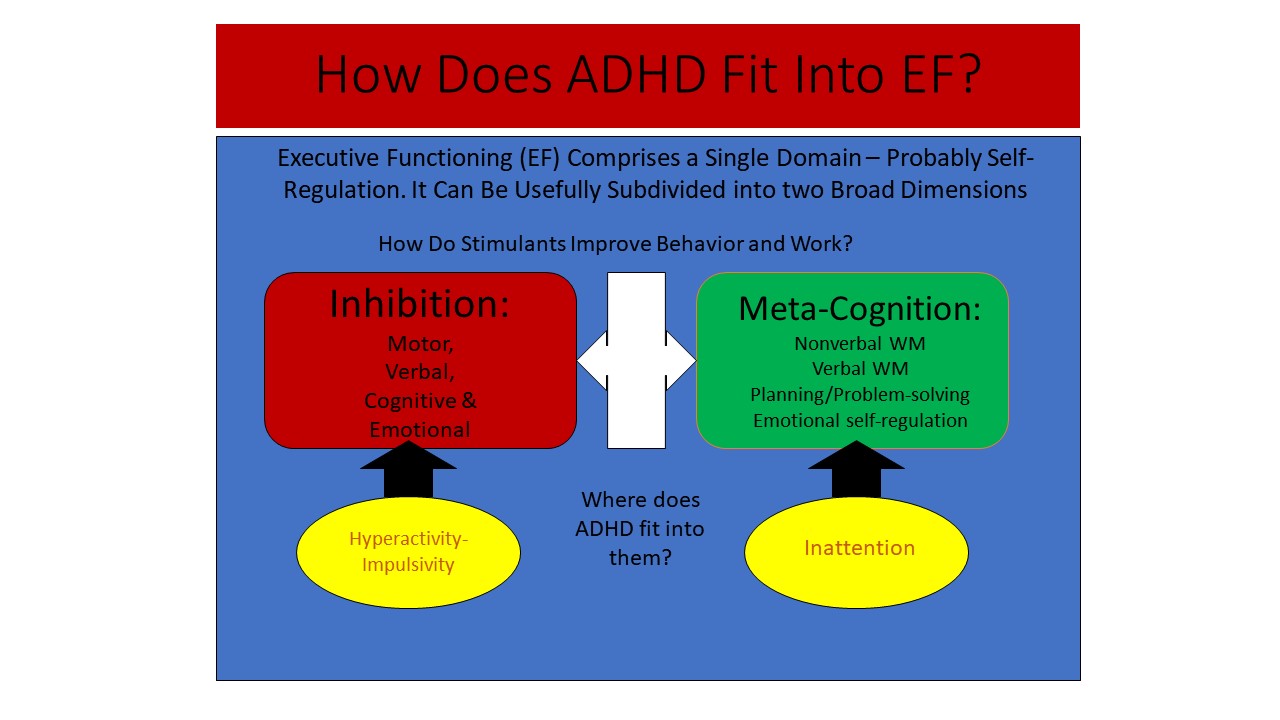

The DSM Criteria Within the EF-SR Theory

The Figure below shows that executive function comprises one primary construct. All research on executive function measures reveals such a single major construct, which I view as self-regulation. That broad domain of executive function can be divided into two: inhibition and metacognition, which, as shown in the figure, can be further dissected into smaller dimensions of executive functions that are partially coupled to each other. The lower half of the figure shows that the two traditional symptom dimensions of ADHD (inattention and hyperactive-impulsive behavior) are simply subsets of the two main dimensions of executive function. This means executive function is both one thing (self-regulation) and many things (it can be subdivided into narrow-band executive functions related to broader bands of inhibition and metacognition).

Is Neuropsychological Testing Useful for Diagnosing Adult ADHD?

Given the role of EF in ADHD, it would seem that EF tests ought to be useful in diagnosing adult ADHD. But they are not. Some of my scientific colleagues argue that ADHD is not a disorder of executive functioning, citing the fact that only a minority of people with ADHD fail their executive function tests and test batteries. Unfortunately, this argument does not explain the serious and pervasive deficits in executive function, self-regulation, and the cross-temporal organization of behavior so evident in daily life in those with ADHD, as shown by self- and other ratings and in clinical interviews. Telling, here, is the substantial body of evidence showing that ratings and observations of executive functioning in daily life are not significantly correlated with the results from those executive function test batteries. So clearly, whatever executive function tests may be measuring, it is not executive functioning in daily life. Critics of the EF-SR Theory of ADHD see this as just more evidence against rating scales; they see the tests as being the gold standard for assessing executive function.

Some also assert the false criticism that such ratings are subjective and so are limited in what they can tell us about executive functioning. I and others see this lack of a correlation between tests and ratings as evidence against the ecological validity of the tests – they are not the gold standard for measuring executive function. Moreover, these tests are poor at predicting impairment in major life activities known to be rife with executive function and self-regulation. Multiple studies using rating scales of executive functioning in daily life clearly attest to the fact that a vast majority of patients with ADHD are impaired in the major executive function domains: time management, self-organization and problem-solving, self-restraint, self-motivation, and the self-regulation of emotions.

A further criticism of the use of psychometric and other tests for evaluating ADHD is that they have given rise to theories about the nature of ADHD that predict nothing of clinically useful consequence outside of their own test results or those tests with highly similar formats. So, the wise clinician is likely to respond to such theories as delay aversion, a limited cognitive energy pool, etc., with "So what?" What exactly does it mean in real life to display, for example, delay aversion on a lab task of that construct other than intolerance of delays on tests? What does it predict about the individuals' life outside the lab and how they are functioning in various important domains? What does it tell us about other risks they are likely to experience given that testing deficit? Does it inform us as to the occupations they should consider or avoid, or the accommodations in work or educational settings they should request?

In sum, what does it say about how to help those patients in relevant and important natural settings where impairments exist? And does it inform us on what other treatments may need to be done to address this core problem, such as with aversion to delay? The answer to them all is a resounding “No.” In other words, you cannot take such deficient test performances to “the clinical bank” because they have no practical cash value, so to speak, for guiding us in helping clients.

The lab tasks are bereft of clinical meaning for providing assistance with differential diagnosis or patient care.

Diagnosing Adult ADHD

In

order to capture all of the relevant information needed to adhere to the DSM-5-TR

diagnostic criteria for adult ADHD as well as to the modifications to it

discussed here, the assessment of a client for adult ADHD should incorporate

the following procedures: an open-ended general interview; a structured

interview of relevant DSM-5-TR disorders; rating scales of adult ADHD symptoms,

executive functioning, and functional impairment; a review of archival records:

corroboration of symptoms through someone who knows the patient well: psychological

screening tests for IQ and learning disorders (achievement); and consideration

of malingering.

These

are listed below and discussed in more detail in the chapter on assessment of

adults by J. Russell Ramsay, Ph.D. in the 2015 edition of my ADHD Handbook

for Diagnosis and Treatment (Guilford Press).

- Use

self-report of ADHD symptoms

- For

current symptoms, use DSM-5-TR flexibly (lower threshold 4+ symptoms)

- For

childhood recall of symptoms, use DSM-5-TR for children (6+ symptoms)

- Mandatory

corroboration of symptoms and impairments by someone else

- Obtain

paper trail of impairments (archival records)

- Establish

the onset of symptoms by age 12

- Chronic

course; no periods of remission

- Impairment

in major life activities (by interview and Barkley Functional Impairment

Scale; Guilford Press)

- Use

average-person standard, not intra-person

- If

impairment came much later in late adolescence or adulthood, explain why

- Use

rating scales of adult ADHD symptoms (Conners scale, Barkley scale)

- Use

rating scales of Executive Functioning (tests are far less sensitive than

ratings; Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Functioning – Adults;

Barkley Deficits in Executive Functioning Scale)

- Rule

out other disorders, explanations:

- low

IQ or Learning Disorders (IQ & achievement screening tests)

- anxiety

or depression as causes of inattention (Symptom Checklist 90-R rating scale)

- Sluggish

Cognitive Tempo/Concentration Deficit Disorder (see Fact Sheet at

www.russellbarley.org)

- Document

comorbid disorders (highly likely to be found) using structured interview of DSM-5-TR

criteria for relevant disorders that seem likely to be present given the

initial interview

- Evaluate

for possible malingering (high in college student referrals)

- Triangulate

results of multiple sources and methods

- Consider

using symptom validity tests

- No

fool-proof means to establish malingering with certainty

The Important Role of Clinical Judgment

As

noted earlier, no precise age of onset of symptoms producing impairment should

be required for a diagnosis of ADHD. The DSM-5-TR recommends age 12 but an upper

boundary of ages 16-18 has been recommended by others based on extensive

research on the issue. Typically, my colleagues and I require corroboration of

ADHD symptoms and impairment from someone else who knows the person well – such

as parents, siblings, or spouses/partners – as part of a clinical diagnosis of

ADHD.

The

clinician conducting the interview should exercise judgment as to

whether the patient’s reports on these matters could be considered to be

realistic or have some veracity. As a consequence, a few individuals may be

clinically diagnosed as having ADHD by the clinician despite their not meeting

diagnostic criteria strictly by their own initial self-report. Others who meet

criteria based solely on their self-report may not be granted the clinical

diagnosis of ADHD. The latter may have other disorders that interfere with attention,

such as anxiety disorders or depression, but do not have the cardinal features

of ADHD (chronic ADHD symptoms from childhood). A moment’s reflection will show

several reasons for why this necessarily has to be the case.

First,

the self-reported ADHD-like symptoms may be clinically judged to be better

accounted for by the presence of another diagnosis (such as dysthymia,

depression, anxiety, substance abuse, marital problem, a situational stressor,

etc.). This is a requirement of the DSM criteria for ADHD that may often go

overlooked in research studies that select their ADHD group merely by rating

scales or solely on self-reported information. This criterion can only be

executed via clinical judgment and knowledge of differential diagnosis and cannot

be incorporated into some mindless algorithm that relies exclusively on

self-reporting.

Second, the symptoms that patients endorse and/or the associated impairments they allege may not rise to the level of being clinically significant in the clinician’s judgment. DSM criteria require that symptoms be both developmentally inappropriate and lead to impairment, which inherently involves clinical judgment. For example, a patient may endorse 14 of the 18 symptoms but the examples of the symptoms given were judged to be clinically trivial and the impact they had in producing clinically significant impairment is either minor or non-existent. Likewise, another patient may give evidence of having no real impairment other than an internal perception that they were somehow not working up to their potential or not being as successful or effective as they thought they should be. In other words, there is no other historical corroborative evidence in these reports that the behavior of which they complain is actually a symptom (abnormal) or that the impairment claimed is so interfering with their functioning that it resulted in being well below the average-person standard discussed above. For example, in the second patient’s case, despite their reported symptoms, they had suffered no problems in school, had received no prior psychological treatment, had received no accommodations for a disorder at school or at work, was happily married, demonstrated no occupational impairment, or failed to manifest convincing social or daily adaptive impairment that in the clinician’s judgment was significant and a consequence of ADHD. In some cases, these are what one might call “ADHD wannabes” who are self-diagnosed before coming into the clinic, typically based on reading a popular trade book on ADHD in adults or hearing media accounts of the disorder and believing themselves to have it. In short, to be eligible for the diagnosis of ADHD, patients have to have a sufficient number of DSM symptoms that in the clinician’s judgment produce clinically significant real-world functional impairment in major life activities.

Third, for the clinician to render an ADHD diagnosis, they need to see fairly compelling evidence of an onset of symptoms sometime during childhood or adolescence, a chronic (unremitting) and pervasive pattern of ADHD symptoms, and impairment that could be reasonably attributed to ADHD. The clinician should not simply record mere self-reported symptom counts or statements of impairment, relying solely on a judgment-free algorithm. It is clear that some patients do not have a good perspective on what constitutes impairment. For example, a patient may have denied having any significant impairment, yet a closer look at their history and school, driving, and other archival records may show substantial struggles in school achievement and deportment, in adverse driving outcomes, in conduct in the community (delinquency), in their job performance or social relationships, or in just managing daily major responsibilities. However, they might have simply chalked it up to "I just hated school" or their job, or their friend or partner, etc., rather than viewing it as stemming from any sort of disorder.

Finally,

there has to be convincing evidence that the symptoms actually developed and produced

impairment sometime during childhood or adolescence. Consistent with the criticisms

raised above about the DSM criteria for ADHD, when many patients are asked about

onset, they have a hard time specifying an exact age. They use phrases such as

"as long as I can remember,” "always," "forever," etc.

Others give evidence of a very poor memory of their childhood and cannot

remember when they first noticed problems, yet they may have given the

clinician other information that helped attach an age to the onset of symptoms

producing impairment (such as getting suspended or held back in first grade).

In addition, some might say their impairment began in high school, yet during

the interview or from inspecting school records it becomes clear that the

impairment had begun much earlier. Our research in fact showed that, on

average, patient reports of age of onset were 4-5 years later than was the

actual onset as recorded in longitudinal studies following them from childhood

to adulthood. And we found that parent reports were no more accurate concerning

retrospective recall of age of onset of their child’s symptoms when judged at

the child’s adult follow-up. Hence, differences could exist in self-reported

perceptions of onset (and even parents’ reported age of onset) versus a

clinician’s determination of onset based on the totality of information

received during the assessment.

Clinical Tips

As noted above, various limitations have been evident in the DSM criteria across the manual's many editions. It's important to be aware of those that persist and how to deal with them to produce the most accurate diagnosis for your patients.

1. Particularly when assessing adolescents (or adults), don’t place so much emphasis on the hyperactive symptoms. Six symptoms out of nine on the DSM list reflect excessive activity, even though for at least the last 40 years impulsivity has been viewed as just as much if not more involved in ADHD as hyperactivity. Hyperactivity is at best reflective of early childhood disinhibition of motor movement and declines so steeply over development that such symptoms are of little diagnostic value by late adolescence and certainly by adulthood. This is one reason clinicians before the 1980s thought the disorder was outgrown by adolescence. Today, the symptom list is losing its sensitivity to detecting true disorder over development.

2. Look for additional symptoms of impulsivity. Poor inhibition should be reflected not just in speech (currently the DSM criteria include only three verbal symptoms) but in other domains such as motor behavior, cognition, motivation, and emotion. Ask parents whether their children:

- Often fail to consider the consequences of their actions;

- Have trouble motivating themselves to persist toward goals;

- Have trouble deferring gratification or waiting for rewards;

- Lack willpower, self-discipline, drive, determination, and “stick-to-it-iveness”; and/or

- Seem unusually impatient, easily emotionally aroused, easily frustrated and quick to anger

None of these aspects of disinhibition or poor self-regulation are included in the DSM-5-TR (or earlier) criteria, yet abundant research shows they are as common in people with ADHD as are the traditional DSM symptoms and, with age, more so than those of hyperactivity. Be sure to ask about them anyway.

3. Use rating scales of ADHD symptoms that have their norms broken down by sex and not just by age. The DSM-5-TR criteria fail to recognize that females may be as impaired as males but at lower symptom thresholds, because (a) females become impaired in certain domains of functioning at lower levels of symptoms than do males, and (b) males were overrepresented in field trials for earlier versions of the DSM, thus making the symptom threshold gender-biased. Research suggests that females in the general population, at least in childhood and adolescence, do not show as much of the symptoms as their male peers, making it harder for a female to meet the DSM criteria even though she may be just as impaired as a male.

4. Think of inattention as metacognitive and other executive function deficits in daily life, particularly those reflecting self-awareness, working memory, poor self-organization, poor emotional self-regulation, and deficient time management. That way, you will know to go beyond focusing merely on DSM symptoms in your assessment of your clients in your interviews and selection of rating scales, among other assessment methods. You will also know in your open-ended initial interview to listen for these types of complaints in order to better help you identify whether ADHD is present or not. You also can better understand the pervasive impact of their symptoms on their daily functioning in major life activities as they explain to you all of the domains in which they are ineffectively functioning. Furthermore, you can better explain the nature of their disorder to them in the feedback conference when your evaluation is completed, allowing them to better understand why their condition is so serious, impairing, and pervasive across major domains of life. It will also help you to appreciate why teens (and young adults) may seem to be outgrowing ADHD, based on DSM criteria, when they are far less likely to be outgrowing their EF-SR deficits and may even be demonstrating increased impairment with age.

5. Don't adhere too rigidly to thresholds for meeting diagnostic criteria when there are clear signs of significant impairment. You are not making a dichotomous decision – disorder or no disorder – or dealing with symptoms whose presence or absence creates a sharp distinction between the two. Keep in mind that ADHD (and EF-SR) is not a category but a dimension. Empirical research asserts that ADHD falls along a continuum in the general population. It is a developmental disorder distinguished more from others by a quantitative difference from normative behavior than as a qualitatively distinct category. So you will see clients who don't meet all of the DSM criteria yet who are experiencing impairment and seek out your assistance with alleviating or at least compensating for it. As practitioners we are valued by society not so much because we can make diagnoses but because we relieve suffering; the rendering of a diagnosis is a means to that end and not the end itself. This means you should diagnose ADHD if:

- Your clients or their caregivers state that the child or teen has a high number of ADHD (and EF) symptoms (above the 20th–16th percentile or so in severity) and there is evidence of impairment in major life activities (harm), even if the client fails to meet all DSM-5-TR criteria; and/or

- Symptoms developed sometime during development, usually before ages 21-24 or so and meet all other criteria for the disorder. DSM-5-TR has raised the age of onset for ADHD from age seven to age 12, but research repeatedly shows that both patients and those who know them well are not reliable or accurate in recalling the age of onset of the symptoms and hence the disorder. It is a mistake therefore to consider age of onset in diagnosing ADHD, all else hitting the stated thresholds.

Impairment is key to diagnosing ADHD.

6. Always consider the source of information when assessing a child or teen for ADHD. The DSM has a requirement for cross-setting occurrence of some symptoms in the diagnostic criteria, but some care must be taken not to confuse that with differences in the reports of others being called on to provide information about the individual. At the individual level of analysis there can be substantial differences in the number and severity of symptoms reported by different observers across the different contexts they supervise. For example, it is well known that parent and teacher agreement on any dimension of psychopathology in children or teens is notoriously low, with correlations averaging just 0.25–0.30. To avoid conflating such natural reporter disagreement with cross-setting occurrence, the DSM should be understood to require that only one or more symptoms need to be present in any given situation as reported by one source, while more symptoms producing impairment may be reported in other settings by other sources. It is the total number of different symptoms endorsed across such reporters that needs to rise to the required symptom threshold (six for children, five for adults). You do not need six (or five) from both sources.

The same caution about conflicting observer reports applies to comparing self-reports by children and teens with ADHD and their parent or others’ reports of their ADHD symptoms. Up until the client is in their twenties, the correlation between self- and other reports is only modest, reflecting low degrees of agreement. The EF-SR theory of ADHD explains this phenomenon: the development of executive functions that create self-awareness lag behind in those with ADHD. Therefore, you should adhere to the newly inserted criterion in DSM-5-TR to corroborate what patients are reporting through another source. If no parent, sibling, or long-term caregiver is available, then available archival records may have to suffice, such as earlier medical/psychiatric records, educational transcripts, or report cards, driving records, work history, etc.

7. Think of – and explain – ADHD as being the diabetes of mental health. DSM-5-TR specifies that impairment may exist in home, educational, peer, or occupational settings, but, because it still focuses on ADHD as deficits in attention or activity regulation, it does not convey how far beyond these domains ADHD has an adverse impact. When you view ADHD as founded in deficits in executive functions and self-regulation, which are requirements for functioning well in most domains of life, you can not only better understand why your clients are struggling to function effectively in so many domains of life and health but you can also better explain to them and their loved ones why that is the case. And why it is imperative that the disorder be treated on an ongoing basis as if it were the diabetes of psychiatry. I return to this point in later chapters that deal with impairment and with adopting the treatment framework provided by the EF-SR theory.

8. Don't assume that ADHD disappears in adolescence. DSM criteria are progressively less developmentally sensitive with increasing age. They lose their capacity to detect true disorder to some extent by adulthood. But if we apply developmentally relative criteria for a diagnosis such as exceeding the 93rd (+1.5 SD) or 98th (+2 SD) percentile relative to same-age peers and requiring evidence of impairment, up to 56% and 49% of childhood cases, respectively, continued to be symptomatic even if not fully diagnosable by DSM criteria. And if we had employed more symptoms of EF-SR deficits beyond the traditional ADHD symptoms, even more cases would be classified as developmentally deviant. Notice that using a developmental approach to diagnosis identifies twice as many cases as being persistent in their disorder as do the DSM criteria.